By Laura Shrake and Ashtin Morgan

At Cardinal Valley Elementary School, the students are like no others in the Fayette County Public School District. Not only because the students at this school are the majority minority, but because of the one-of-a-kind program that stems from this demographic.

Cardinal Valley is the area of Lexington just west of downtown, stretching down Versailles Road roughly from Red Mile to Mason Headley roads. This area’s demographic is a majority Spanish-speaking population primarily from Mexico, the same demographic reflected at Cardinal Valley Elementary.

Because of this, the school piloted a program two years ago to help this population learn literacy skills in their native language, hoping to improve the students’ classroom performance.

“After several years with a lot of problems, we decided the students needed to start learning in their native language,” said Ali Coves, a teacher in the program at Cardinal Valley Elementary School. “They were in the classrooms and weren’t getting anything from the teachers.”

Coves, also a native Spanish-speaker, said that many kindergarteners lost almost a whole year of learning because of the language barrier, and by the time the students reached third grade their literacy skills were at a kindergarten or first-grade level.

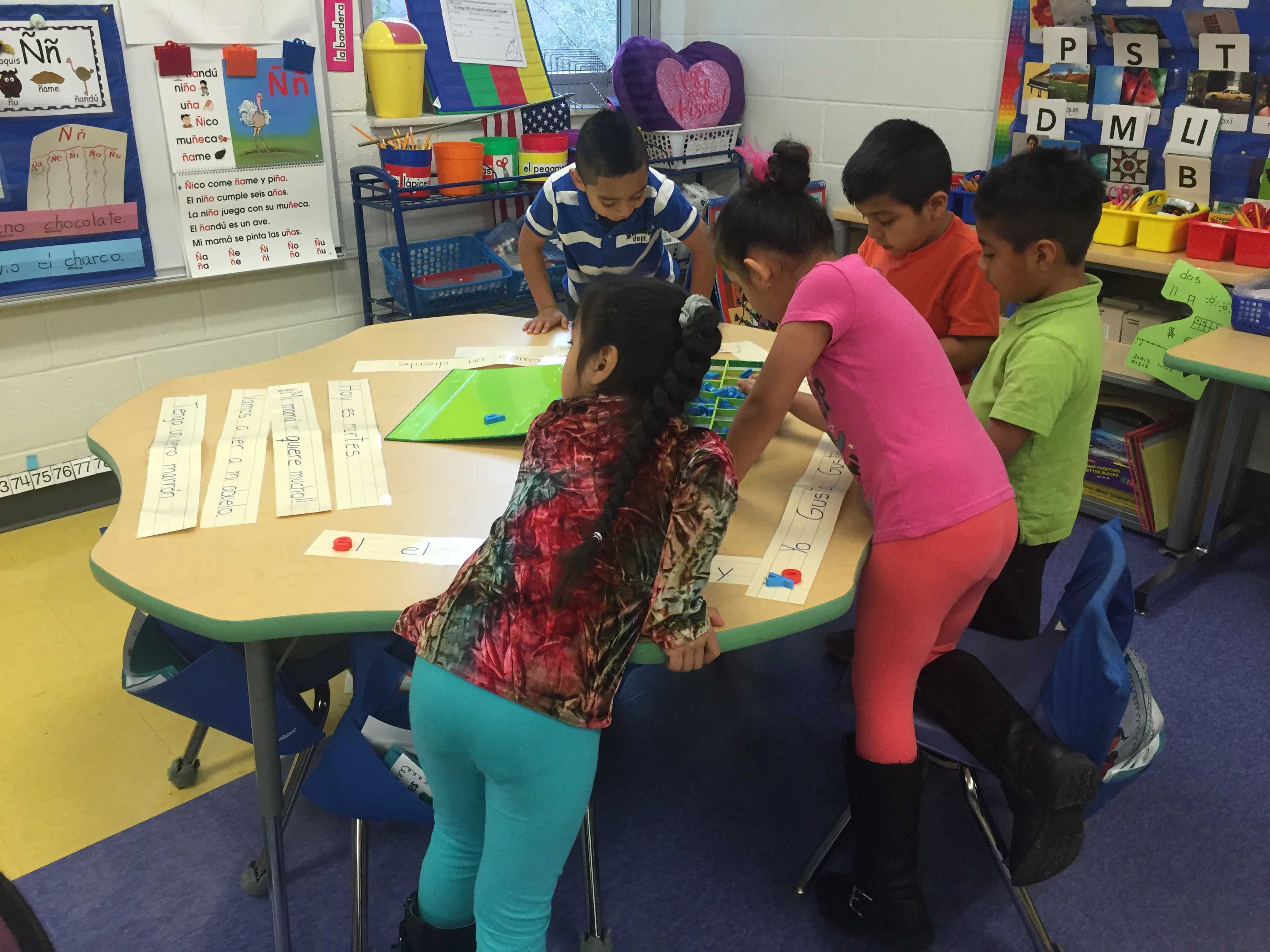

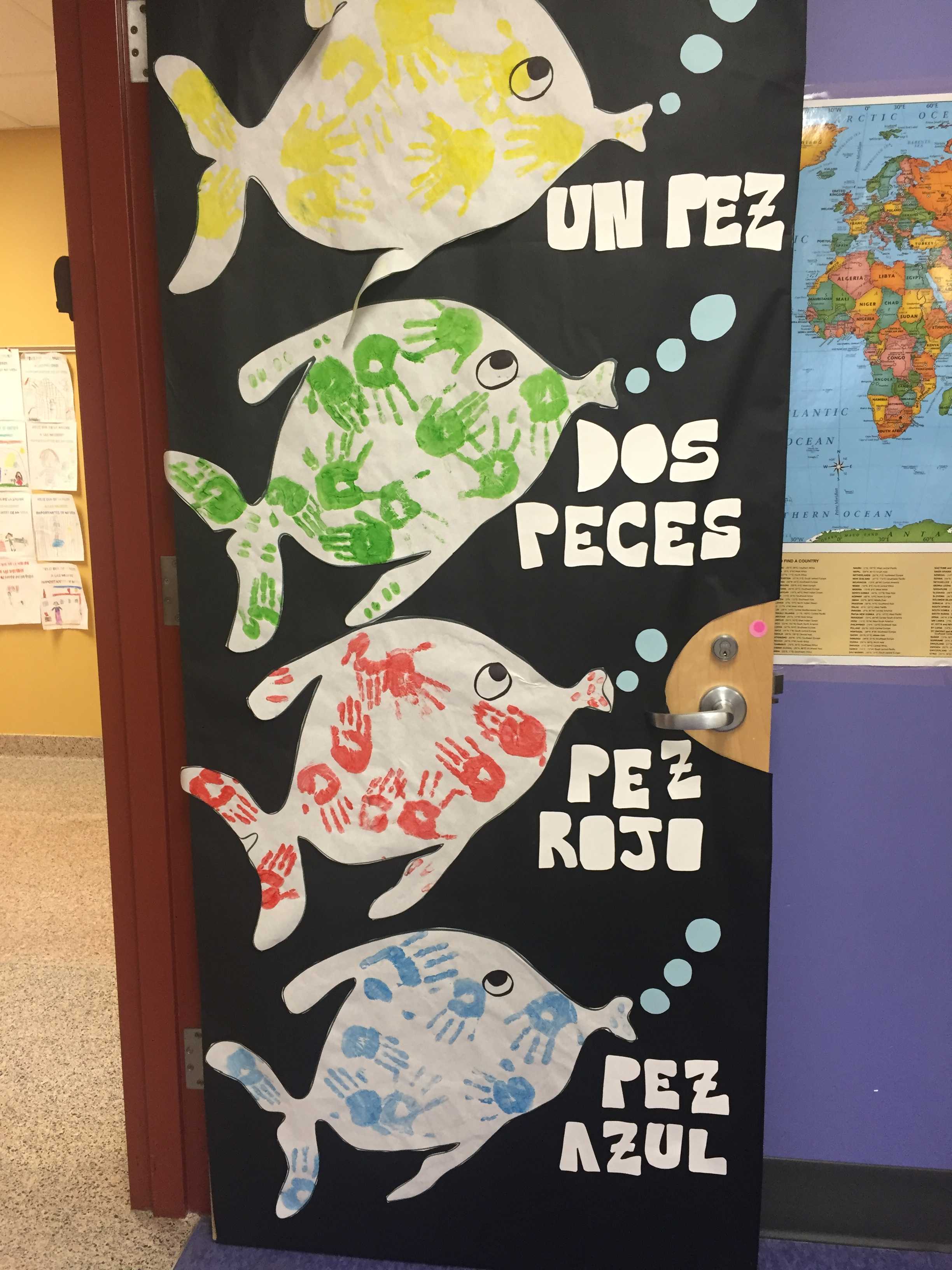

This program, known formally as a dual-language one way, is the only one in Kentucky. It started last year with two groups in kindergarten. Coves said the students in these classrooms are all Hispanics with little knowledge of the English language. The program is designed so that these students first learn to read and write in their native language before learning the same literacy skills in English. 80 percent of their day in the classroom is spent in Spanish and the remaining 20 percent in English to begin familiarizing them with the second language. Coves is hopeful they will excel in all subjects to prepare them for testing.

The goal of a program design like this one is to, as Coves said, bridge the students’ language from Spanish to English. The group that started in the program last year is in first grade this year, where the ratio of Spanish to English changed to 70-30. By third grade, the ratio will be 50-50 Spanish to English.

“It’s working really good,” Coves said. “Last year they learned how to read and how to do math skills, and this year it’s amazing how they are learning to read in English because they already knew how to do it in Spanish.”

Coves noted that many research studies are finding the same results of Cardinal Valley’s immersion program—learning how to read and write first in one’s native language eases the student’s ability to become literate in a second language and in many cases helps the student learn the second language faster and more comprehensively.

Coves said the program follows the same state-mandated curriculum and common core requirements as any other classroom. The students are not behind in content, although they may be behind in the language.

The program is new, so the exact formula for how the program functions will continue to evolve as the first group progresses through it. One change Coves said the program may consider making is moving the 50-50 ratio to second grade instead of third so the students are prepared for the standardized testing (in English) during that year.

Alan Brown, an associate professor of Spanish applied linguistics at the University of Kentucky thinks that move may not be the best strategy in the long run.

“If your whole model of education is trying to prepare a kid for a third grade test, to me that’s very short-sighted,” Brown said. “The long-term benefits of developing literacy skills in both languages far outweighs whatever score they might get on a third grade standardized test.”

But Brown recognized that this focus is a product of our societal values.

“The districts are under so much pressure with these standardized tests that we can lose the forest through the trees,” he said.

The ideal manner of bilingual education, Brown said, is two-way dual immersion. In this type of program, English speakers are immersed in the 80-20 ratio and are part of the same classroom as the Spanish speakers. When the demographics are mixed the students can learn to lean on each other and become more culturally diverse in the process. It also keeps the teaching method from being subtractive, which can lead to the loss of the students’ heritage language—a loss that Coves called “extremely sad,” and Brown called “a travesty.”

Neither the program at Cardinal Valley Elementary nor the immersion programs at Liberty and Maxwell elementary is exactly this type. Liberty and Maxwell immerse the English-speaking students in the non-dominant language (Spanish), while Cardinal Valley immerses the Spanish-speakers into the dominant language (English) and phases out their dominant language over the course of their primary schooling.

Coves said this program has been successful thus far. She’s seen the results of first learning literacy in the students’ native language. Doing so not only helps preserve their heritage language and the language they may need to communicate at home and with extended family members, but also aids them in their English language education and helps them learn the dominant language.

At a national level, Brown said bilingual education is not getting nearly enough attention. What many may consider “bilingual education” is not considered such by most scholars in the field.

“To really reap the benefits of bilingualism, you have to go all in,” he said. “ … Bilingual education should train students in both languages over the long term. It makes sense to develop the native and heritage language as much as you can.”

Categories:

Spanish immersion program brings benefits, questions of bilingual education

May 5, 2016

0

More to Discover